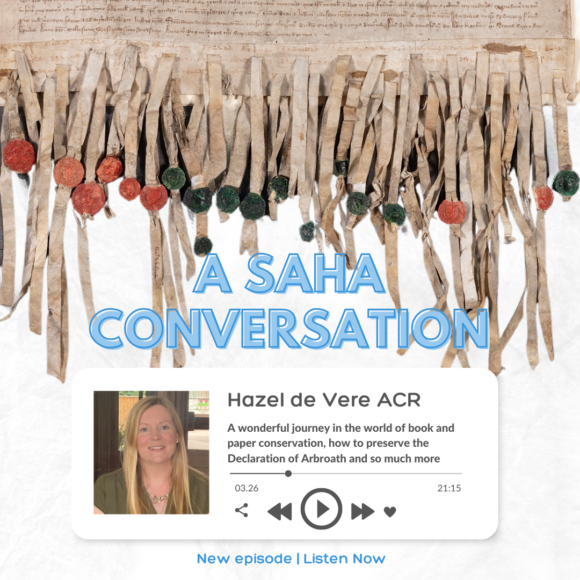

SAHA has launched a podcast series to reflect on the contribution of arts and humanities to society. We will speak with a range of inspirational individuals who have experienced first-hand the value of arts and humanities in their lives and their careers.

Our first guest for the SAHA Conversation series is Dr Clark McGinn. Clark is a leading consultant in the global mission-critical helicopter industry, based in London but advising international clients. He was educated at the University of Glasgow, where, in addition to graduating MA (Hons) in Philosophy, he was a noted student debater, founding the World Student Debating Competition, winning the Observer Mace and selected to represent the UK in the annual ESU Debate Tour of the USA. After university, he embarked on a thirty-year career in corporate banking and capital markets in London and New York, which pivoted in 2004 into helicopters. After creating RBS’s rotary wing business, he built the Captive Dublin lessor for the largest helicopter operator (CHC) and later, the global sales and relationship team for Waypoint Leasing. He has worked as an independent subject matter expert and consultant to leading investors and operators since 2018. Clark holds the Fellowship of the Chartered Institute of Bankers. He is also known as a speaker and writer on Robert Burns, having earned his PhD from Glasgow on the history of the Burns Supper. He is currently an Honorary Research Fellow of the Centre for Robert Burns Studies and was awarded Fellowship of the University of Glasgow for his charitable support of its alumni Burns Supper programme over many years.

In this SAHA Conversation, Clark reflects on the value of an education in philosophy today and he explains how this degree has helped him in his career in the banking sector. We discuss his passion for Robert Burns also and the bard’s role in bringing people together the world over also.

Resources mentioned in this episode

Transcript

Transcript

01:37 Cristina: Good morning and thank you for joining our discussion today. To start our talk today I wanted to ask you when did you decide to do an arts and humanities degree? What made you choose that particular subject?

01:59 Clark: Yeah, that’s a good question. At school, at high school, I was very much in the science stream and when I was looking to come to university my first choice was to come to Glasgow to read theoretical physics as it was called ‘natural philosophy’… and that old it was called, it wasn’t even called physics then. In the run up to coming to university in those days there was a general bursary examination that school students from all over Scotland participated in for a week in Glasgow. And one of the papers was a general paper, which had logical and philosophical questions in it, that were totally alien to the high school curriculum. And I can remember one question was ‘an irrational fear is a fear that is not rational’, ‘John fears that his fear is an irrational fear” is that rational?’ And that really caught me in philosophy cause it’s very like theoretical physics, you have to parse the strands apart. And so when I came up to university all those years ago I did natural philosophy, mathematics and – because at Glasgow, and I’m not sure if it’s still true now – but philosophy and physics could be taken either as science subjects leading to BSc or arts subjects to lead to an MA. And I took as my third subject in my first year moral philosophy and that just entranced me. The analytics of the same strength as mathematics and theoretical physics but it seemed to probe even deeper into making the brain work and making you think so I moved after my first year increasingly into philosophy and then graduated in Moral Philosophy as an MA. So that is how I got, sort of, dragged into it.

03:48 Cristina: That’s a nice way of putting that ‘dragged into it’. Looking back now how do you think your degree helped you in your career?

03:56 Clark: I think there are two things, Cristina. One, at school and at university my hobby was debating and so philosophy helped you construct arguments that analysed data to build a persuasive case. So when I was graduating, I joined Lloyds Bank on its Fast track graduate scheme and I found very quickly, if you are in the financial services world you can’t be as good a farmer as the farmer to whom you’re lending money. You can’t be as good as the shopkeeper or the post bank, ’cause they live their business every day, so the skill in banking is then to step back and analyse what the key risk elements are in that business. Sometimes the ones that the farmer won’t recognise because he or she is living in that every minute of the day and so philosophy for me … a lot of my colleagues had done economics or mathematics or law, and I found that I could ask questions in a different way that would bring us back down to the building blocks of what that business was and by taking it apart then you can build it back together again. Great fun. I think the debating element helped. Obviously, Glasgow is one of the greatest debating universities in the world. I had the great good fortune to win the British and Irish national competition with my dear friend, the late Charles Kennedy. And so the combination of being able to analyse and then being able to present came together hand in glove.

05:26 Cristina: Thank you. Would you recommend students to study philosophy today? Thinking of all you’ve said before.

05:34 Clark: Yeah. Cristina, I think it is just like mathematics, it is just a fundamental wiring of the human brain. Thinking back in my undergraduate career I knew some lawyers, I knew some scientists who’d do a philosophy course as well as a science. And I think it helps you broader the manner of thinking. And today we’re in a world where clarity of thought, you know LinkedIn, Facebook, there’s just a lot of noise out there. So I think even more than ever we really need to have the internal mechanisms inside our own minds to be able to strip away the noise and see what’s important in life. Philosophy gives that. It’s a building block for law, for jurisprudence. It’s a building block for economics, Adam Smith was a professor of moral philosophy and he invented economics. Philosophy is right at the bedrock of all human endeavour.

06:31 Cristina: It can lead in a sense to different careers, you don’t actually need to be a philosopher if you’ve studied philosophy.

06:39 Clark: That’s a very good point, I don’t know how many paid philosophers there are in England. I’ve got a feeling there’s not too many in the Times 100 rich list. But as you say it’s like linguistic skills, I think it’s part of the hard-wiring of the brain, so it adapts the way that your mind works and then, like I did in banking, you adapted to your professional needs and that helps you understand people, processes, businesses, it helps you to understand the world in a different way.

07:12 Cristina: Something that is quite special to your profile is your passion for Robert Burns. You have written several books on the subject and you gave numerous addresses on Burns Night. Can you tell us a little bit of how that interest developed?

07:31 Clark: Of course, Cristina. I born and brought up in the town of Ayr in the South West coast of Scotland where Burns was born. In fact, Robert Burns spent two weeks attending my high school, Ayr Academy, which is the oldest continuously teaching school in Scotland, it was founded in 1233. So the school was very traditional and one of the things you can imagine was round about Burns Night. So every single pupil had to learn a Burns poem or a song, and recite it or sing it. And the rules were: it should be a whole poem, if it was less than 30 lines, or you could use 30 lines from a bigger poem. Me being the apprentice philosopher I worked out very quickly that Burns wrote some four-line poems so that met the rules. The rector, the head teacher wasn’t very happy that somebody so obviously … being lazy to put it bluntly. And so for the school’s Burns supper when I was 15 he said ‘You’re going to do the address to the Haggis’. I’m going to make you learn that poem and perform it in front of the school. The next year I did the ‘Toast to Lassies’, the next year I did the ‘Immortal memory’ and in my last year I did the ‘Toast to the School’. So every year since I was 15 I’ve spoken in from one to 12 Burns supper a year and through that I’ve met many different people all modes and manners of men and women in 17 different countries, 40 cities. The Sidney Opera House was one venue I performed in. But everywhere I’ve gone people enjoy the party that is Robert Burns, the poetry, the emotion, the story that brings – again, I use philosophy to bring out themes in Robert Burns. Not just telling a story but trying to link it into what we’re feeling today. So that has been a real living part, a great honour. I worked with the Centre for Robert Burns Studies at the University of Glasgow. And in fact I did a part-time PhD on the history of the Burns supper under Professor Carruthers so it has been one of the very big strands in my life, still is.

09:43 Cristina: How has this intersected with your professional career?

09:48 Clark: That’s a great question. It really, really has. It came to a head when I was working in New York City for the Royal Bank of Scotland. RBS bought National Westminster Bank, a very big English bank, and there was a big question, how do we tell people about the Royal Bank of Scotland? Now nowadays we know that the Royal Bank of Scotland got into a lot of trouble, then it was a very different bank. And so what we resolved in doing was a Burns supper in Houston, Texas, and a St Andrews’ Night dinner in honour of Robert Burns in New York in November. And I became the RBS cultural ambassador, as well as doing my day job, and it was great fun, it was really a chance to say, this is what Scotland is about. And when you start peeling away – that was really where my interest in the history of the Burns supper came – because as early as 1812 there was a Burns supper in Baltimore, Maryland. By 1820 New Jersey and New York were having Burns suppers, Philadelphia and Boston close behind. So wherever people had an interest in humanity they found an interest in Burns’ poetry right from the time of his early death. And it’s just a great joy to feel that it wasn’t just me standing up in speaking, I’m just part of a 200 and odd-year tradition that many people, 9 million people as Murray Pittock’s research assesses, 9 million people every January celebrate Robert Burns and I’m one of them. And that says pretty good philosophy to me.

11:24 Cristina: It’s wonderful. Moving to Scotland I’ve discovered Burns night and this tradition, I read a little bit about it and realised just how much it means for people to celebrate it, in Scotland, but as you mentioned outside of Scotland also, it’s one of those traditions that brings people together all across the world on that particular day. Could you tell us a bit more about this recent Robert Burns project that you were involved in?

11:53 Clark: The Centre for Robert Burns Studies decided to map global Burns suppers, a very interesting project. Paul Malgrati was the guy doing the heavy lifting and we launched that this January. So now people can click on the map and find out if there’s a Burns supper near them, we hope to keep adding to that and turn it into a sort of living database. So very exciting. It comes back very much to what you were saying that Burns is Scottish but he’s not exclusive, he chimes the thoughts and hopes of men and women, boys and girls all over the world. And that’s why it’s not just expats who support him, but if you go to India or South Africa, to Brazil you’ll find local celebrations about Robert Burns, possibly with some Scottish people who are tagging along, you know that Scottish people like turning up for a party and a drink. But oftentimes it’s the local inhabitants who are celebrating Burns as much as us.

12:54 Cristina: That’s wonderful. Thank you very much for sharing all of these with us, it’s been a very interesting discussion.

13:00 Clark: Cristina, thank you for inviting me and good luck with the rest of the podcasts. Thank you very much.